Overview: Peacebuilding Support for Myanmar, 2010–2020

This paper explores how international aid donors supported peace processes in Myanmar, 2010–2020. It first presents an overview of international engagement in Myanmar and foreign aid flows during that period, then discusses the factors that affected support for conflict resolution, presenting eight key findings. These findings are relevant to development practitioners, diplomats of donor countries, government officials, and others supporting peace in Myanmar or elsewhere. Information is drawn primarily from interviews with national and international stakeholders who supported peace processes in Myanmar in the years in question. The preexisting literature also informs this assessment, enabling the research team to identify key findings and the implications for future peace support. The first paper in this series, The Context for Building Peace: Entrenched Challenges and Partial Reforms, assesses the context in which foreign aid for peacebuilding was provided, and further detail on background and methods are included in the paper series introduction.

The foreign aid described here comprises primarily official grants and concessional loans from countries in the Global North (members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD) as well as multilateral organizations including United Nations (UN) agencies, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank. Support from China and other Asian countries is also considered.[1] The Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) between the government of Myanmar and eight ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) was the most significant step towards peace in the period of study, and the focus of most peace-related foreign assistance at that time. This paper looks mainly at support associated directly or indirectly with the NCA, while also considering interventions linked with other steps to curtail conflict, including longstanding bilateral ceasefires with individual EAOs, efforts to resolve tensions in northern areas of the country where EAOs did not sign the NCA, and other measures such as community-level programs not associated with a specific peace process.

International Relations with Myanmar and Foreign Aid Flows

With the advent of reforms in 2010, Western countries began to reconsider their ties with Myanmar. What the OECD calls “official development assistance,” which had waxed and waned in the country since 1948, soon started to flow.[2]

Following elections and the formation of a quasi-civilian government under Thein Sein, Myanmar rapidly renewed its engagement with the full spectrum of official donors, including Western countries and multilateral institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the regional Asian Development Bank. The country went from being the 79th-largest recipient of aid in 2010 to the seventh-largest in 2015. By 2017, it was the third-largest recipient per capita in the region—behind only Cambodia and Laos, which have far smaller populations. Expectations were for close, sustained engagement with the international community.[3]

Diplomatic relations with Western countries had been characterized mainly by the imposition of sanctions in response to human rights abuses and the suppression of democracy. Many donors reduced their development cooperation with Myanmar during the period of successive military regimes that started in 1962. During this period, Myanmar looked for support from Asian nations instead.[4] Japan, followed by China and other neighboring and regional countries, were the most important providers of foreign aid in the form of grants, concessional loans, and other assistance such as training and exchanges of officials. As China’s economy and influence grew beginning in the late 1980s, it became Myanmar’s primary external partner and influence. Beijing built a relationship with the military government while keeping links with EAOs operating along the shared border, and backed strategic public and private investments in mining, dams, transportation, and farming.[5]

In the early 2000s, Myanmar’s military government was slowly implementing some internal reforms while maintaining political control. A key priority was to improve foreign relations, especially with Western countries, in response to growing concern about the overbearing influence of China. Aid flows gradually increased at this time, including support for infectious disease control through the Three Diseases Fund. A new constitution was introduced in 2008, soon after mass protests had been violently suppressed in what became known as the Saffron Revolution. The constitution laid out partial reforms for a semi-democratic system, while also defining the continued influence of the military over politics. Foreign aid flows from Western nations and multilateral agencies started to change in 2008 after the worst natural disaster in Myanmar’s recorded history, Cyclone Nargis, devastated the delta area south of Yangon and caused an estimated 140,000 fatalities. While local groups mobilized to support affected communities, the Myanmar government opened the doors to international humanitarians. In a separate sign of increasing openness, India bolstered its economic relations with Myanmar in 2008 by negotiating the Kaladan River Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project, aimed at boosting trade and commerce.[6]

Following elections in 2010 that were deemed illegitimate by many observers, reform accelerated with the release of political prisoners including Aung San Suu Kyi, and steps to encourage the return of nationals from the international diaspora. As demonstrated progress increased international confidence, sanctions were eased. Western donors added to their in-country presence, scaled up their development assistance, and gradually expanded their work with government departments. The cancellation of the China-funded Myitsone Dam project in 2011 was regarded as a watershed, both distancing the Myanmar government from Beijing and indicating a more responsive approach to public interest.[7] Aid flows rapidly grew as new frameworks were adopted and agreements were signed. Two events in 2015 ensured that the trend toward normalizing relations with the West would continue. The signing of the NCA by Myanmar’s quasi-civilian government and eight EAOs was followed by democratic elections that were convincingly won by Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD).

OECD data shows that between the start of 2011 and the end of 2015, Myanmar received USD 13.7 billion in aid commitments. Over USD 6.5 billion of past debts were forgiven. Japan, the World Bank, the United Kingdom, and the United States were the largest contributors. Programs operating at a national level made up the bulk of aid contributions, with the health, energy, and transport sectors receiving the most funding.[8]

Problems stemming from Myanmar’s entrenched conflicts persisted, however. The NCA process was only a ceasefire and did not include many EAOs; the power of elected civilian leaders was strictly limited by the 2008 constitution; and the military remained independent and unaccountable. While the NCA could have been a foundation for further progress towards peace, events took a different turn. The newly elected NLD government struggled to build a more inclusive peace dialogue out of the ceasefire agreement, and changes instituted by the new government led to a hiatus in the peace process.

The Rohingya crisis of 2017–2018, in which the Myanmar military was accused of ethnic cleansing and/or genocide by Western countries and at the UN, effectively ended the brief honeymoon period and generated a perception among many aid donors and diplomats that Myanmar’s entrenched problems were far from resolved. Following the 2020 elections, a second term of office for the NLD offered some new hope for the peace process, as discussions on a revamped peace architecture emerged. At this point, the military surprised international observers by taking over the government in a military coup in February 2021 and setting off widespread conflict.

Supporting Peace Through Foreign Aid

Following the end of the Cold War, increased operational space for aid agencies, combined with concern over rising levels of subnational conflict in many parts of the world, provided a basis for new approaches to peacebuilding. Early emphasis was placed on the need to ensure that aid funds at the very least “do no harm,” given the depressing track record of policies and projects that have unwittingly contributed to organized violence.[10] Conflict sensitivity soon became established as a working approach, and agencies developed specialist peacebuilding units.[11] International guidelines published by the OECD laid out how to help prevent violent conflict through development cooperation.[12]

A significant, global body of knowledge has been acquired from the complex interactions of foreign aid, peacebuilding, and conflict. By the time of Myanmar’s reforms, most aid agencies had experience operating in conflict-affected contexts, even if they were not familiar with working in the country itself. Some looked to support Myanmar’s emerging peace process where it was useful, and many bilateral donors included it in their diplomatic engagement, often harnessing development funds to do so. Longstanding connections with international campaigners, the Myanmar diaspora, and opposition groups within the country provided the basis for programming. Initial work often focused on southeastern Myanmar, along the border with Thailand, where humanitarian operations had worked for many years, and donor support typically flowed through specialist international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or other intermediaries.

Initiatives proliferated across a range of operations and sectors involving support to government, civil society, and EAOs:

- Mediation and dialogue support. Often low-profile and high-level, initiatives worked to support discussions on ceasefires, peace processes, and political dialogue and offer negotiation advice to government and EAO leaders. Agencies supported by donors included the Euro-Burma Office, Nyein Foundation, the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, the Center for Humanitarian Dialogue, the Sasakawa Peace Foundation, and Intermediate.

- Confidence-building initiatives. Many programs were established in conflict-affected areas to address ongoing tensions, reduce barriers to peace, provide a peace dividend, or placate potential “spoilers.” These often involved local development or humanitarian activities. Some initiatives worked directly with EAO and military leaders to support ceasefire and peace-process negotiations; others worked with grassroots organizations. Examples include work supported through the US-funded Kan Lett, the Norwegian-initiated Myanmar Peace Support Initiative, the Japan-funded Nippon Foundation, and many Myanmar NGOs.

- Direct funding for peace architecture. Donors, typically following requests from the Myanmar government, were willing to support elements of the peace process. This included paying for leaders of EAOs to attend vital meetings and providing other resources, backing the government-led Myanmar Peace Center, and realizing elements of the NCA including the Joint Ceasefire Monitoring Committee (JMC) and Liaison Offices for EAOs.

- Capacity building and training. Assistance was provided at many levels through intermediaries. Programs offered expert advice, courses, seminars, and study tours for government officials and leaders, EAOs, NGOs, women, youth and community groups, and ethnic organizations. Initiatives covered awareness-raising, research, policy development, and support for technical aspects of the peace process, as well as related subjects such as decentralization, natural resource management, democracy, gender equality, and accountability.

- Large-scale development initiatives in conflict-affected areas. Large programs, often funded by multiple donors, were expanded to conflict-affected areas. Examples include the 3MDG health fund, the Livelihoods and Food Security Fund, and the Myanmar Education Consortium. Some donor-funded initiatives were implemented by local NGOs such as Metta Development Foundation and the Kachin Baptist Convention, while others focused on infrastructure, government services, or private-sector economic growth.

- Research and analysis. Donors funded many assessments, often to build their own understanding. They invested resources in “conflict sensitivity” work to inform specific programs and their overall approach. Grants were also given to national institutions, such as the Salween Institute, the Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security, and the Karen Human Rights Group, to develop their research skills for conflict monitoring and analysis and key NCA political dialogue topics.

- Public information to enhance citizen awareness of the peace process. Donors were late to fund this field, but supported “knowledge, attitude, and practices” studies to understand public opinion on the peace process and enhance social cohesion. Assistance supported skills development in media organizations like Burma News International and promoted peace through radio drama (BBC Media Action) and cultural interactions among the general public.

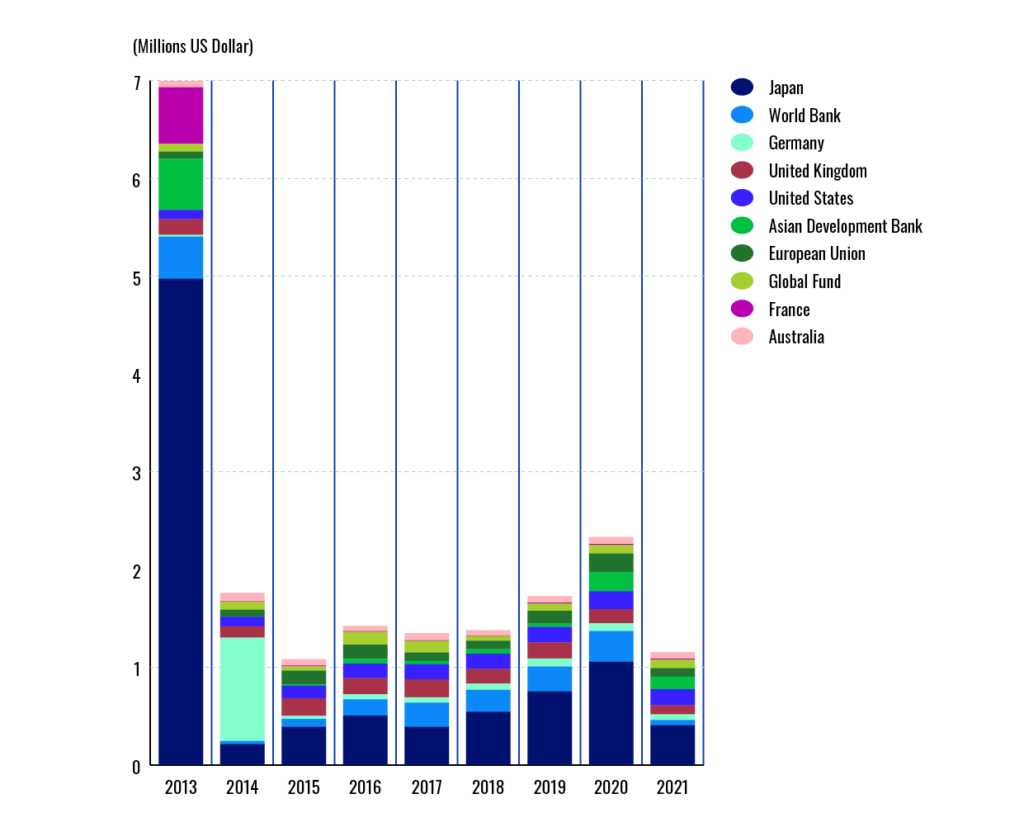

As reforms took hold, international relations improved, and the peace dialogue continued, peace-related aid commitments grew rapidly, from USD 11 million in 2010 to USD 18 million in 2012, and to over USD 120 million in 2015.[18] Overall, peace support was extensive, making vital contributions in many fields. Yet it remained a very small proportion of overall foreign aid to Myanmar, accounting for between 0.8 percent and 3.6 percent of all aid funds over the years 2012–2021 (figures 2).

The highest levels of international support for peace (defined by the OECD as “Conflict, Peace and Security”) occurred in 2015, reflecting the broad investments by the international community in developing and operationalizing the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA). While the drop in 2016 may simply have been a result of the large sums already committed in 2015, the later decline in commitments mirrors the declining confidence in the peace process. Problems were beginning to emerge openly in 2018, as several key EAOs suspended their participation. This deadlock left many international donors unsure how to continue seeking progress in peacebuilding outside of the NCA framework, and caused them to reassess their relationship with the Myanmar government in light of military actions against Rohingya in Rakhine State.

Peacebuilding aid is typically delivered through relatively small, focused programs whose cost to the donor is low when compared to major infrastructure programs or nationwide health and education initiatives. Peacebuilding investments in Myanmar were relatively small (tracking with global trends throughout this period), given the absence of international institutional involvement such as deployment of peacekeepers or major post-conflict development initiatives. Figure 3 describes some major peacebuilding programs operating during this period. Three of these were funded by multiple donors, and all operated across different conflict-affected areas of Myanmar.

|

Name |

Donors |

Key Focus |

|

Myanmar Peace Support Initiative |

Norway, Finland, the Netherlands, Denmark, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, the European Union, and Australia |

A short-term effort to support ongoing ceasefire negotiations and provide peace dividends to help build confidence and establish a conducive environment for the separate political processes. |

|---|---|---|

|

Kann Lett |

USAID Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) |

Phase one: to increase participation and inclusion in reform and peace processes and to address critical impediments to the transition. Phase two: to deepen and sustain reforms and foster legitimate processes for pursuing peace. |

|

Nippon Foundation[19] |

Japan |

Sustained Incremental Trust Establishment and Support (SITES). This approach engaged state governments in dialogue together with EAOs to build trust between principals by jointly implementing programs to address the needs of conflict-affected communities. |

|

Peace Support Fund, later the Paung Sie Facility |

United Kingdom, Australia, Sweden |

Support to small-scale, gender-responsive, demand-driven initiatives that promote social cohesion in Myanmar communities. |

|

Joint Peace Fund |

United Kingdom, USA, Finland, Japan (initially), Norway, Switzerland, Canada, the European Union, Germany, Italy, Australia, Denmark |

The overarching goal, until 2020, was an “inclusive peace…reached through agreements and strengthened stakeholders, institutions, and processes,” thereby strengthening conflict-management mechanisms, dialogues and negotiations and national and subnational participation in the peace process. |

High impact can still be achieved in various ways through well-designed and carefully implemented programs, particularly those with a specific or local focus (see box 3). The impact of aid for peacebuilding was especially high for local organizations. The creation of the USD 100 million Joint Peace Fund in 2015 offered major opportunities for civil society organizations to advance their objectives. Equally, there were real risks that new grievances would arise from decisions over funding allocations.

At the same time, major flows of funds are significant, whether aid expenditures or commercial investments. In conflict-affected areas of Myanmar, private- and public-sector development initiatives have long exacerbated conflict tensions. Central authorities have intentionally used development funds as a means to expand control through new infrastructure initiatives such as roads and dams, extending public services, and resettlement schemes.[20] Meanwhile, well-connected private investors in mining or agriculture have been able to act with relative impunity.[21] This background made the agenda of conflict sensitivity across aid programs a core priority for civil society, many local inhabitants, and some EAOs. The NCA reflects these concerns, stating clearly that EAOs have the authority to receive foreign aid in their areas of control, and that EAOs and the military need to coordinate “to improve livelihoods, health, education, and regional development for the people.”[22] Box 4 below further explores the issues related to cross-border aid and convergence.

Key Findings on Foreign Aid Approaches

Finding 1. Donor assumptions about the transition to peace

International aid donors were insufficiently cautious about persistent tensions and the risks, particularly for the NCA process. These risks could have been mitigated by more locally-grounded understanding of the context and less reliance on Western models of reform.

From the perspective of Western observers, the broad transitions and reforms underway in Myanmar beginning in 2010 had three interlinked components: economic liberalization, political democratization, and peacebuilding through the emerging NCA process. This triad of reforms fit wider expectations of progress towards a post–Cold War model sometimes termed the “liberal peace.” The apparent alignment of Myanmar with this vision reassured diplomats, donors, and politicians of positive, linear progress towards peace and a more inclusive, democratic form of nation-building.[24]

The assumptions of the liberal peace model have been widely criticized as overly prescriptive, narrow, and naïve.[25] In the case of Myanmar, uncritical adoption of this approach failed to consider complex domestic elements. For example, there was no guarantee that more democracy would improve core-periphery relations or address the deep-seated concerns and grievances of EAO leaders. It may even have had the opposite effect, depending on electoral and other political systems, the presence of checks and balances to protect minority voices, and the degree of authority enjoyed by leaders below the national level.[26] There was therefore no guarantee that political reforms in Myanmar would enable further progress beyond the NCA. The NCA had to confront the long history of central military control while the wider reform process was limited by the conditions of the 2008 constitution.[27]

More thought, and more suitable frameworks for supporting peace, might have better addressed these contextual complexities. For example, the approach outlined in the World Bank’s Pathways for Peace report recommended designing an approach based on the interactions among a different triad: contextual structural factors, key actors, and key institutions.[28] Most donors (and many domestic interests) had a limited grasp of these nuances and the complexities of a real-world peace process.

This occasional blindness to nuance among donors was more problematic when working closely with the government. Myanmar was, for the most part, a functional state with a strong background of independence, and foreign aid agencies had to respect the norms of sovereignty. The same respect did not have to be shown to EAOs, given their status as nonstate actors and the asymmetry of the conflict.[29] After the 2015 election, Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD government sought more control over foreign aid flows. In 2016, the government established a Joint Coordination Body to scrutinize funding allocations and spending limits on activities related to peace process implementation.[30] The government view was that the relatively opaque volume of aid provided for peace activities should be more tightly under their control and allocated to the main NCA process.

Finding 2. Understanding the problems rooted in the civil-military divide

Donor programs showed mixed awareness of the tensions between central military and civil elites. The unstable environment was characterized by entrenched tensions at the highest levels of politics, and government effectively relegated the peace process to a secondary level.

It became increasingly apparent to donors that military leaders acted independently and that civilian officials were mostly focused on their relationship with the military. As the 2021 military takeover emphatically demonstrated, expectations that reforms had created a stable platform for a peace process were misplaced. Reaching agreement with the military to reduce their political role remains Myanmar’s most abiding challenge. Aung San Suu Kyi sought to improve her position by pushing against the military’s political role while also siding with them at opportune moments. Released from decades of military-enforced house arrest, she played on her family’s military credentials, often recalling her father’s historical role as a founder of modern Myanmar and its military by referring to “my Tatmadaw.” In 2019, she defended military leaders from charges of genocide against the Rohingya at the International Court of Justice. This ongoing political struggle tended to marginalize other concerns, especially the interests of ethnic leaders and minority populations, including the Rohingya.

In this challenging environment, donors moved too quickly to support the government with standard development projects unsuited to the context. An example is the World Bank’s high-profile Community-Driven Development project, whose initial steps upset observers by appearing to assume that conflict tensions had subsided.[31] Problems emerged when the program moved into minority areas of Myanmar, including a conflict-affected township in northern Shan State where the government had a track record of using development initiatives to establish control of contested or recently acquired territory. Wider consultation with ethnic leaders at this initial stage could have identified difficulties. Over time, the World Bank responded positively by seeking advice from specialists and engaging intensively at the local level. Partnering with NGOs at pilot sites, rather than working solely with the government, helped mitigate the challenges facing field operations in areas of live conflict. Gradually improving relationships with government counterparts also enabled project managers to navigate tensions and find solutions.

Finding 3. Recognizing the importance of China

China exerts the greatest external influence on Myanmar, and it was pursuing its own approach that reduced the scope of the NCA process. Western donors in particular struggled to understand China’s broad involvement in conflict reduction activities within the larger history of cross-border relationships and China’s foreign policy position toward rapid development in Myanmar.

All the countries bordering Myanmar have significant policy and investment interests there, but China remains the most influential external power, even after the reengagement of several Western countries. Aung San Suu Kyi paid a priority visit to Beijing after the 2015 elections, traveling there before visiting Washington, D.C.[32] The Chinese government retained close links with military and civil leaders in Myanmar, while also maintaining their strong historical relationships with EAOs, especially those close to its border like the powerful United Wa State Army. China provided assistance for some aspects of the NCA process but was never fully involved.[33] Both Chinese officials and Myanmar’s military appeared to discourage the involvement of northern EAOs in the NCA.[34] China did later put pressure on them to attend Union Peace Conferences following a formal request for assistance from Aung San Suu Kyi.[35] China also worked to limit the influence of the West close to its border. US involvement was especially sensitive to Chinese officials, who on one occasion advised the US Ambassador in Yangon not to visit Kachin State.[36]

While China’s importance in Myanmar was broadly understood by Western donors, aid officials at ground level were typically unsure how to respond. As one China expert noted,

The West did not sufficiently recognize the trends in China’s support to strengthen Northern EAOs, having no strategy in place to tackle it, let alone understanding how these conflicts might change and affect the NCA.[37]

Despite a few diplomatic efforts with northern groups and with China, Western donors were indecisive in building those relationships possibly for fear of upsetting the Myanmar military or civil government.[38] Unsurprisingly, aid workers and officials working in Myanmar were poorly situated to address the effects of deep-rooted rivalries. Some Western diplomats saw their presence in Myanmar as a geopolitical coup on China’s doorstep, in line with political and security measures elsewhere to counter Chinese influence in the region. Others were unsure how to engage, partly because Chinese officials rarely participated in donor coordination activities.

Most Western aid donors did not have a nuanced understanding of the strategic interests guiding Chinese policy in Myanmar or the complex relationships between China and the EAOs. China’s interest in access to the Bay of Bengal, the importance of related investments and infrastructure, their discussions with northern EAOs, and how this affected their support for the NCA were also poorly understood. At times, China was seen one-dimensionally as a “spoiler” to be avoided rather than an important actor. At a more conceptual level, peace support seemed to presuppose an “international community” with a shared vision. The failure among Western officials to consider China in this group contributed to overly optimistic assessments of the peace process and to the neglect of alternative, non-Western approaches to peace in Myanmar (see box 2 on Japanese support to Myanmar and the Nippon Foundation’s peacebuilding work.)

Finding 4. Pacing engagement

Donors struggled to take the long view, accept setbacks, and adapt approaches to mitigate risks.

From 2012, aid agencies rapidly established a presence in Myanmar, often moving long-term posts from Thailand to Yangon. Some arrived on a wave of optimism that led to a “terrible free-for-all at the beginning,” with donor agencies pursuing and protecting their own areas of interest and respective comparative advantages.[39] This gold-rush mentality sometimes led to short-sighted decisions—for example, the rapid phase-out of village-level nongovernmental programs, developed over many years, once it became politically acceptable to work with the government. The title of a 2013 study of foreign aid to Myanmar, Too Much Too Soon, succinctly captured these concerns.[40]

The excitement of the rapid reforms, especially after the 2015 elections, also resulted in donors treating Myanmar as a post-conflict environment, despite evidence that signed ceasefires were not being upheld and violence was growing in northern Shan State, Rakhine State, and elsewhere. Expectations of how long it would take for a genuine, comprehensive peace to emerge and what was needed to unravel and address the political complexities of Myanmar, were also unrealistic. While many individuals were aware of this institutional over-optimism, the strong international commitment to achieving liberal peace and reform in Myanmar tended to mute overt criticism. Critics were labeled nay-sayers or cynics who needed to “get with the program.” This attitude made it difficult to moderate expectations, and reduced the ability of international actors to effectively support local peacebuilders.

Many donors were slow to adopt flexible approaches that learn from failure and adapt to changed circumstances. With their unrealistic expectations, they were ill-positioned to acknowledge inevitable failures or recognize ways to build on the experience. An instructive example was the haste with which some donors dismissed the JMC as ineffective rather than critically assessing its contribution and potential to support change (see box 6). In the face of a process carrying high expectations, the response of donors to non-functioning mechanisms was to continue support while bemoaning the lack of progress—in effect, “flogging a dead horse” in the forlorn hope that it might bring change.

Finding 5. Working around capacity constraints

The need for reliable delivery partners constrained the support provided by international actors. While existing NGOs and CSOs did play a vital role as delivery conduits and sometimes important advisors on context and strategy, such partnerships could divert national actors’ attention from their core work, or spark local tensions over funding access and reach.

The need for rapid expansion of programming highlighted the lack of credible partners and initial low capacity to deliver interventions according to international development norms and expectations. Very few partners for program delivery, whether inside or outside of government, were able to run large programs without training and institution-building. As one donor noted:

There were a number of options, but none of them was ideal. What were the trade-offs, and how willing were respective capitals to follow one path or another? It was a question of hammers looking for recognizable nails to hit! Some of the funds were “hammer defined.”[44]

The Myanmar government’s lack of experience working with the international community was challenging for all stakeholders. On the one hand, donors found it difficult to work with government institutions due to the lack of long-standing ties, the opaque systems, and the resulting concerns about effectiveness, accountability, and transparency. It was equally hard to work with EAOs or their associated CSOs, also due to their inexperience with donor processes and to concerns about the risk of supporting armed actors. This situation reinforced the common trend of seeking NGO intermediaries or delivery partners to support ethnic capacity building and to offset their own fiduciary, legal, and reputational risks. Donors interviewed noted the potential for consequent distortions, including the possibility of warping the way such organizations were perceived by stakeholders and shifting the focus of their work.[45]

One complex feature of the peace process was international support for negotiation specialists. Two main types of expert were involved: high-profile individuals who tended to provide advice during rapid fly-in-fly-out visits, and lower-profile individuals who provided advisory and capacity support over longer periods. Ethnic leaders often considered the long-term specialists more effective, as they offered context-driven advice and invested the time required to generate trust. Individual specialists tended to be senior, male, and from a European background, and there were few efforts to broaden the pool. Many of the local or national groups promoting dialogue, like the Peace-talk Creation Group in Kachin State, offered more diverse participants and alternative perspectives.

Donors’ search for delivery partners also led to the uneven provision of aid—through established relationships with civil society groups in Karen communities, for example, but with fewer effective partners elsewhere. Since information flows often followed established funding relationships, donor agencies’ understanding of the peace process was skewed toward areas where they were already most engaged.

The rapid growth of Myanmar’s international development sector from 2012 onwards significantly altered the civil society sector. Positive contributions to building civil society are noted in box 9, but respondents also said that short-term funding—rarely more than annual cycles—tended to create “project machines” that reflected donor funding practices rather than recipients’ own understanding of the situation. The weight of donor compliance and administrative regimes shifted their focus and deployment of human resources, and led to the creation of large, dominant organizations which were preferred recipients over smaller, local groups or those not confirming to Western organizational forms (see also box 8 on “projectization” and “timescapes”).

Finding 6. Peacebuilding approaches did not substantially include women

Foreign aid projects and programs in Myanmar often included stipulations regarding women’s participation, but many of these ultimately fell short of gender-transformative outcomes through a combination of operational challenges and lack of will.

Structural gender inequality is present across all social and political domains, including peacebuilding institutions and activities associated with conflict reduction. There were varying levels of women’s participation in key stakeholder groups, with many EAOs considered to be more open.[46] Organizations focused on women’s rights and leadership were present nationally and locally, and there were some well-known cases of Myanmar women playing a key facilitation role in dialogues and negotiations. Within civilian government, political parties, and the Myanmar military, however, female representation in decision-making was close to zero (Aung San Suu Kyi being the notable exception), resulting in the absence of women from the top table in peace discussions.

In this context, foreign aid actors could play an important role in amplifying calls for greater gender equality from Myanmar stakeholders, linking their efforts and objectives with global evidence and good practice from other peacebuilding contexts. There were significant challenges to putting this into practice, beyond the difficulties of getting traction amongst senior national decision-makers. Substantive inclusion of women and changing gender norms were not prioritized as core objectives of peacebuilding programs, limiting the scope of real change on these issues. For example, quotas for female participants in donor-funded activities were often the main indicator for gender inclusion. While the practice of setting benchmarks for female participation represents a positive step, these quotas were set largely without regard for who the participants were and whether they were able to make contributions, doing little to influence the content or outcomes of the discussion.

The tendency toward superficial approaches to gender inclusion also affects the dynamics between donors and implementing partners. Women-focused and women-led organizations are best placed to undertake the long-term work of creating change in gender norms; however, these groups are often small and amorphous, making it more difficult for them to access foreign funds through cumbersome and technical administrative processes. In addition, funding for gender equality and social inclusion is often constrained by relatively short funding windows, with limited scope to support institutional strengthening such as through core funds. For more detail on the challenges around gender inclusion in peace support, see the paper titled Women, Peace, and Security Funding Dynamics in Myanmar, 2010–2020.

Finding 7. Applying conflict sensitivity across aid programs

Despite a significant body of experience and international good practice amassed over the past few decades, the extent to which donors incorporated conflict sensitivity into their strategies and funding mechanisms in Myanmar varied. More could have been done to mitigate possible negative impacts from donor supported activity at national and local levels.

Conflict sensitivity approaches are commonplace within aid agencies seeking to operate effectively and safely in conflict-affected areas worldwide.[47] To implement conflict sensitive approaches, these actors need sufficient capacity to understand the contexts in which their programs are operating, to assess their possible impacts on the conflict, and to take these .into account in program design of the project. Careful and sensitive consultation with local stakeholders is typically a critical part of the design process. Conflict sensitivity also encompasses the policy arena and the need to consider how national and donor policies influence conflict-affected areas and conflict dynamics. As noted earlier, it was easy for donors (and government officials) to overlook conflict-affected parts of Myanmar, or to falsely assume that the NCA process had ended violent incidents, when working in Yangon or traveling to and from Naypyitaw, well away from affected areas.[48]

Integrated approaches. Some aid agencies took significant measures to integrate conflict sensitivity into their programs. For example, Sweden’s government donor agency Sida contracted advisory support for at least five independent pieces of work, one assessing its ability to consider conflict sensitivity across its portfolio and others to inform funding decisions on specific initiatives. Similarly, the UN-run national health fund invested in assessments of its strategic approach in conflict-affected environments before employing specialist advisors, supporting the capacity of implementing partners, and carefully navigating relationships with the government and EAOs.[49]

Poor practices. Many documented examples of insensitive practice exist. Questions have been raised over the direct and structural impacts of broad approaches including humanitarian support for the Rohingya in Rakhine State, especially for those confined to camps and denied freedom of movement. Specific projects have also raised concerns, such as Japanese support for government planning in southeastern Myanmar that failed to consult local stakeholders or meaningfully take into account the complex governance arrangements in large swathes of contested and EAO-held territory (see box 7 below). One factor in these errors was international and domestic stakeholders’ superficial understanding of the NCA, particularly the interim arrangements, which increased the likelihood that development approaches would undermine the NCA agreement. The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census was especially controversial due to ongoing conflicts across the country, intercommunal violence in Rakhine, and generalized distrust of the government. Underlying tensions persisted over citizenship rights and the arbitrary system of religious and ethnic categories, established by past military leaders, that the census applied. Technical support for the census was provided by a UN agency that initially paid insufficient attention to conflict sensitivity and risk management. According to its own evaluation office:

Despite several warning signs, UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund) support underestimated the sensitivity of the question on ethnicity given the country’s political context… The generalized view is that UNFPA could have done more to understand the local context and sociopolitical implications of the technicalities of the census.[50]

Equal treatment in the NCA process. Donor engagement in the NCA process itself was sometimes insensitive. Some EAO leaders felt that foreign aid exaggerated existing power asymmetries, as comparatively high levels of support to government reinforced their ability to determine the way the process unfolded.[51] A history of political marginalization of ethnic areas and their exclusion from the benefits of development have been fundamental drivers of the conflict in Myanmar. While foreign agencies need to respect government sovereignty universally and recognize the primacy of the central government at the national level, a failure to balance these obligations against the legacy of unequal relations may have further alienated EAOs and reduced the chances of a sustainable agreement.

Finding 8. Avoiding compartmentalized thinking

Aid programs often operate in separate silos—isolated projects that fulfil their stated reporting and financial requirements without linking horizontally. This problem is especially acute in conflict environments, where it sometimes seems that donors and the UN operate on separate tracks through their development, humanitarian, and conflict response mechanisms. Ensuring coherence across these fields (the “triple nexus”) is difficult to achieve in practice.

These challenges are partly a product of the results-oriented funding mechanisms that characterize foreign aid, which work better in a relatively stable environment—for example, when a signed peace agreement is already in place. Projects and their management tools can be developed when there is a well-defined structure to “hang” the funding on, but they are not well suited to complex, unpredictable political processes due to their lack of flexibility or responsiveness to rapid changes in direction and needs (see box 8 on “projectization” and “timescapes.”)

The constraints and consequences of inflexible planning mechanisms and annual budget cycles were significant in Myanmar. For example, donors noted that the Joint Peace Fund (JPF), which became the main conduit of support for the NCA process, had based projections for its activities, negotiations, and dialogue on experience with the Thein Sein administration, which ended in 2015. Continued progress at the same pace was unrealized, and budgets were left unspent, due to the mismatch between expected and actual progress.[53] Some positive experiences also emerged. For example, the European Union and others were able to provide essential early support for the Myanmar Peace Centre, a crucial peace institution led by a former minister of the President’s Office, Aung Min. Other donors were also able to deploy flexible funds at some critical moments.

Donors established shared funding mechanisms to support the peace process, such as the JPF. In theory this kind of joint approach would increase coordination, maximize efficiencies, pool knowledge and expertise, and make it possible to assume risks without exposing single agencies. While the JPF was successful in bringing together an impressive 11 separate donors, many donors continued to support bilateral initiatives outside the shared fund, potentially reducing the value of the shared approach and in practice adding to, rather than reducing, a complex and overlapping array of funding mechanisms and projects.[56] Rather than increasing levels of risk tolerance, shared multi-donor mechanisms can end up being constrained by the lowest appetite for risk across contributors.[57] Furthermore, risk assessment often looks solely at the initiative in question rather than considering the risk and opportunity costs of not intervening. In this regard, EAO leaders noted that international support had enabled them to participate in the NCA process in a more significant way by providing funds which these groups might otherwise have generated in more predatory ways.

Observers close to high-level mediation initiatives also criticized poor coordination, one respondent noting that “all these efforts, particularly informal dialogues, were not sufficiently joined together, nor did they link with the Chinese envoy.”[58]

Compartmentalized thinking also hindered peace support in other ways. One strong example mentioned during interviews was the lack of investment in building public awareness of the peace process, especially among the Bamar majority. Information campaigns to build support for dialogue are a common component of foreign assistance in similar settings, and such measures might have established a stronger political foundation for the peace process at the national level. Yet, peace support in this field was minimal.[59]

The effects of compartmentalized aid approaches were seen elsewhere, too. Aid agencies tended to pigeonhole Kachin State as a humanitarian zone due to their ongoing support for displaced communities. A more holistic analysis of a complex situation, involving peace overtures as well as ongoing armed clashes, could have enabled agencies to pursue aspects of the “triple nexus” by integrating humanitarian, development, and peace actions in protracted crises.[60]

The most striking example of thinking and working in silos involved responses to the acute crisis affecting Rakhine State and its separation from the NCA process. Rakhine State endures a combination of tensions. First, relationships with the central government are complex and contested, as in other ethnic areas of Myanmar. Second, the acute mistrust and polarized attitudes surrounding the treatment of Rohingya and other Muslim minorities in Rakhine State generates a related yet separate source of violence and injustice. The Myanmar military wanted to ensure that Rakhine State, and the conditions endured by Rohingya in particular, were considered separately from other parts of Myanmar, and Western donors were largely discouraged from working there except for carefully controlled humanitarian assistance.[61] By regarding Rakhine State as a separate entity and passing over acute subnational tensions, donors were able to work in a complex environment and maintain their relationship with the government. The problems associated with this compartmentalization became more obvious as the Arakan Army gained territory and then as violent displacement of Rohingya into Bangladesh led to international accusations of military-led genocide. Donor peacebuilding programs in Rakhine State were conducted outside the framework of the NCA process and tended in many cases to prioritize humanitarian aid and local social cohesion initiatives with limited links to the wider political reality.[62]