A Short Overview of the Context

Given the vast body of existing material on Myanmar’s conflicts and peace processes, only limited background information is provided here, sufficient to enable any interested reader to comprehend the insights offered by interviewees and other stakeholders. Those who seek additional depth and detail are referred to alternative sources along the way.[1]

Myanmar has been beset by political contestation, center-periphery tension, and internal conflict since its independence in 1948, and a broad consensus on how the country should be governed has proved elusive. National-level tensions have persisted, leading to repeated political crises, underdevelopment, and violent suppression of mass protests. The national situation following the 2021 military coup rapidly became acute amid widespread resistance across much of the country. In the first half of 2022, more incidents of violence against civilians by state forces operating domestically were reported in Myanmar than in any other country in the world.[2] At the subnational level, long-running conflicts also continue between ethnic nationality groups and central authorities, especially the military. This report focuses on these conflicts and specifically on international support for efforts to solve them through dialogue during the decade before the 2021 coup. The tensions at national and subnational levels intersect, as seen in the range of responses by ethnic leaders to the 2021 military takeover, and yet the conflicts at the subnational level also have their own distinct dynamics. Many of Myanmar’s border regions are home to ethnic nationality or religious and linguistic minority communities that make up around one third of the country’s total population, in contrast to the Bamar ethnic group which is primarily concentrated in central and lowland areas.[3] Over time, violence in these areas has come to be characterized as ethnic conflict related to the political, social, and economic marginalization of minorities along with the wider lack of legitimacy of successive Bamar-dominated authoritarian regimes.

Power holders have failed to create a nation state that unifies and reflects the various aspirations for autonomy and self-governance of ethnic groups and their leaders, instead pursuing a centralized, authoritarian approach. The 1947 Panglong Agreement, despite its lack of fulfilment, is still cited by many as the basis for a future Myanmar federalism, and is seen by some ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) as an historical reference point in their continued struggle over equality and self-determination: it is listed in the first article of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), and it informs the concept of the 21st Century Panglong Union Peace Conference.[4] The very basis of ethnic nationality aspiration in Myanmar is contested given that successive military regimes adopted outmoded and overly rigid identity categories as a central aspect of state organization. This perpetuated the long-term dominance of those who were Buddhist, Bamar, and male.[5]

Although the military has kept trying to extend its control through force, assimilation, expansion of Bamar state authority, and other means, it has also pursued efforts to end hostilities with leaders of nonstate armed groups, primarily through negotiations and bilateral ceasefires. For example, General Ne Win conducted a “nationwide peace parley” in 1963–64; and in 1981, negotiations were undertaken between the military and the Communist Party of Burma (at that time a strong, armed force), leading to a series of ceasefires. These efforts were neither comprehensive nor sustainable, however, and the result has been such a proliferation of EAOs that by 2016 there were more than 20 such groups operating across the country in addition to other paramilitary groups affiliated with the Myanmar military such as Border Guard Forces and militia.[6]

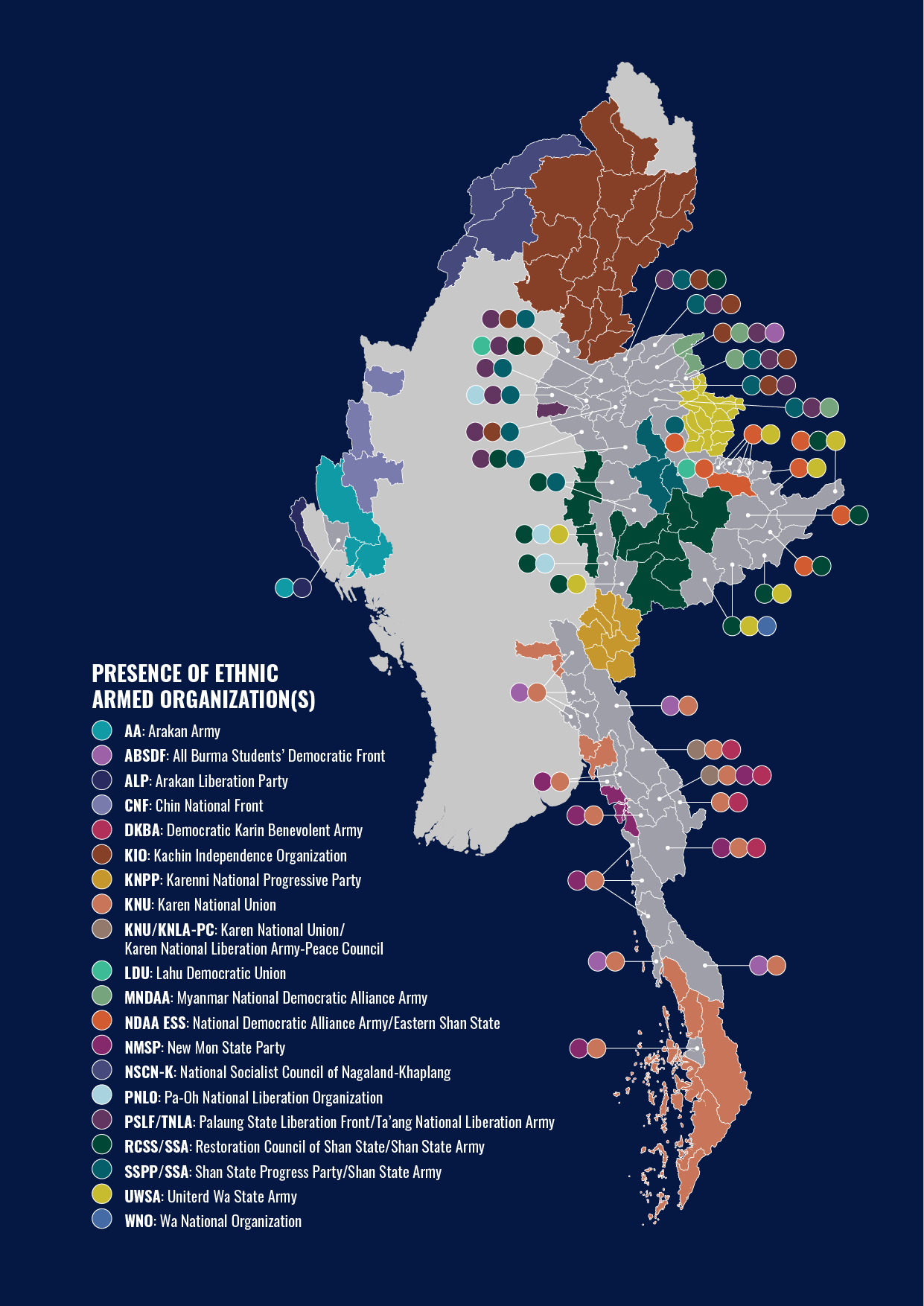

In 2016, a research team from The Asia Foundation identified areas affected by active or latent subnational conflict in at least eleven of Myanmar’s fourteen states and regions (figure 1). Each of these contested areas, which represented 118 of Myanmar’s 330 townships and almost one-quarter of Myanmar’s population, hosts one or more EAOs that challenge the authority of the central government. Armed violence, and the presence of these groups, which are normally affiliated with one of Myanmar’s many ethnic communities, are not just a concern for remote border zones of the country: some affected areas lie within 100 kilometers of either the capital, Naypyidaw, or the largest city, Yangon. Many of the older EAOs operate both political and military wings, though fighting capabilities vary hugely. The larger groups control swathes of territory and have major economic holdings. The strongest armed wing of an EAO, the United Wa State Army, can mobilize as many as 30,000 troops.[7]

The late 1980s and 1990s saw a series of bilateral ceasefire agreements with several EAOs, forming the foundation for the development of the NCA under President Thein Sein.[8] Alongside these conflict-management efforts, the contested 2008 constitution introduced some elements of democracy while further entrenching the political influence, durability, and independence of the military. Meanwhile, a combination of war fatigue and the possibility for change encouraged some military and EAO leaders to seek a more enduring resolution. Thein Sein’s inaugural speech was considered by many to be the first time a leader of the Myanmar military had expressed regret and sorrow for the “Hell of untold miseries” that people had suffered over many decades.[9] Striking a chord with civil society actors and key EAO leaders, the speech signaled a major change.

Starting in 2010, the country experienced numerous reforms, including the first general election in 30 years, resulting in a quasi-civilian government (run by a military-aligned party and made up of retired officers); the release from over two decades of house arrest of long-time pro-democracy advocate Aung San Suu Kyi; the gradual lifting of economic sanctions by many countries in the Global North; and rapid growth in the country’s business sector. In some parts of the country, people’s living conditions improved rapidly. These changes, together with the signing of the NCA in 2015, generated significant excitement among international diplomatic and development actors.

In the process of developing the NCA, leaders of participating EAOs undertook several reflection meetings in late 2012, from which the key elements of the document emerged.[10] Existing bilateral agreements between the military and each EAO were analyzed, the common features were compiled, and missing elements addressed. For example, existing negotiated ceasefires included no implementation mechanisms, nor had they led to any broader reforms. As a result, the NCA refers to both. As one key participant in the process recalls:

First, we drafted the code of conduct and the principles… but in addition to a ceasefire, the EAOs wanted the NCA to be the beginning of a constitutional process, so there had to be an element of systems change. This then became a three-part structure and considerably more than just a ceasefire: the ceasefire, the political dialogue commitments, and finally the transitional arrangements, including the governing structures, with the latter being the most contentious part to implement.

Three drafts emerged from this process: that of the EAOs and counter-drafts from the Myanmar Peace Center (MPC) and the military, to be reconciled using a single-text procedure. The resulting foundational document was considered the skeleton of the change process, which would identify and address future fault lines.[11]

The development of the NCA was a remarkable achievement, even if many of the envisioned components did not eventuate. The NCA process also served the important function of moving the discussion of ceasefires and the peace process squarely into the public sphere and the purview of the government. Prior to the NCA process, negotiations had involved small, discrete groups of stakeholders, resulting in agreements more easily reached and administered, but narrower in scope.

Another laudable development of this period was the establishment of the MPC, with support from the European Union and the government of Japan. The MPC was to be a quasi-governmental body that coordinated all peace initiatives and participants, serving as a platform for conflict protagonists and stakeholders to meet and negotiate in a designated setting—a first in decades of negotiation efforts.[12] Many senior staff were Bamar exiles who had returned to Myanmar after studying in the Global North. A range of issues could be discussed, and research on peace issues was undertaken under its auspices and control. Communications and problem-solving were high on the agenda, and the team reportedly learned how to navigate networks and leverage influence and power to move agendas forward towards the NCA. For example, if there were blockages on the military or quasi-civilian government side, a judicious call to a senior person from a well-known monk might unlock intransigent positions.[13]

The MPC was pragmatic in approaching different groups when issues needed to be discussed or EAOs were ready to progress. Recognizing that building trust was a fundamental part of the process, a number of initiatives were taken forward during this period:

- Significant investment in “normalizing” relationships and breaking down communication barriers between parties. Recognizing each other’s humanity involved sharing meals and socializing in informal settings.

- Proactivity and responsiveness. EAO requests for meetings or discussions always received a positive response, even if they required immediate travel to Chiang Mai or other locations.

- MPC as a safe haven. EAO leaders were told to “consider the MPC as your home” when in Yangon. Linked to this were other efforts to assist EAO leaders with personal challenges. For example, if a family needed medical care or some other assistance, it was facilitated and the costs were covered.

Another telling detail of the negotiations, described by an ethnic leader, was the Thein Sein government’s straightforward approach. Chief negotiator Aung Min reportedly had a four-step progression of possible responses to proposals from his opposites: “I will take responsibility for this, please go ahead”; “I need to check with the commanders”; “I have to go back to the president”; and finally “I dare not cross this line.” EAOs could return to Aung Min, however, with further arguments to convince him to move forward.[14] The initiative was considered an interesting development, in which the military-aligned government created a separate space to think differently, interpreted at the time as an indicator of a new openness.[15]

At the same time, this period brought new tensions and challenges. Areas not covered by NCA dialogues could risk being left out of promised progress, while certain groups faced pressures to sign, perhaps against their own judgement. In Kachin State, a 17-year ceasefire broke down in 2011, while EAOs in northern Shan State fought one another for control of lucrative territory along the Chinese border. In Rakhine State, political oppression of the majority ethnic community by Bamar elites produced violent incidents, while the Muslim Rohingya community experienced long-standing persecution, multiple atrocities and mass displacements in the region from 2012 onwards. This culminated in a multidimensional crisis in 2017–18, leading to the forced movement of over 750,000 Rohingya people into Bangladesh and the region, and has been categorized as a genocide.[16] As early as 2016, national and international observers were beginning to view such developments as signs that reforms were not taking hold. Though peace talks continued to attract financial and political support, including the Union Peace Conferences (UPCs) of 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2020, there was a clear sense that progress toward tangible peace had stalled even before the military takeover of February 2021.

Further challenges arose from the military’s inconsistent treatment of EAOs in the NCA process, inviting some to participate and excluding others, creating divisions between groups.[17] On the EAO side, there were various positions on signing the ceasefire or joining the political dialogue, a further complication. Some EAOs already had bilateral ceasefire agreements with the military or were in negotiations with them. There were also differences between groups as to which had been involved in the various ethnic summits or participated in or been observers at the UPCs. In addition, a range of armed actors did not qualify as EAOs—militia and other groups whose activities would not be covered by the ceasefire agreement. This differing treatment had implications for the NCA process and how much each group was willing to trust the military. Through these variations, it is possible to discern several broad categories of EAOs according to their peace-process participation (figure 2).

|

Signatories to the NCA |

Non-Signatory EAOs |

|---|---|

|

Groups invited to sign by the military/government |

|

Groups not invited to sign by the military/government |

|

|

|

Signatories to the NCA |

|---|

|

|

Non-Signatory EAOs |

|---|

|

Groups invited to sign by the military/government |

|

Groups not invited to sign by the military/government |

|

Notes:

- (a) The KIA, KNPP, and SSPP felt that their conditions for signing the NCA were not met.

- (b) The UWSA and NDAA showed little interest in signing the NCA.

- (c) The NSCN-K was undecided, the role of India being a complicating factor.

- (d) The LDU was originally not invited to sign the NCA, but later allowed.

- (e) The ANC was not invited to sign, but reportedly would be allowed to participate in the political dialogue process.[19]

Critical Aspects of the Peace Process

This section unpacks the contextual complexities of recent peace efforts, offering greater understanding of their challenges and successes. It lays out the positions and actions of domestic actors, while those of foreign governments and aid donors will be further discussed in the second paper of this study, Lessons from Foreign Assistance for Peacebuilding in Myanmar. The kind of complexity explored in this section is sometimes referred to as a “wicked problem,” an issue that is particularly difficult to solve due to the many connected and even contradictory factors that produced it and the difficult and often changing requirements for resolution. Myanmar’s political, social, and economic landscape in the early 2000s certainly fits the definition of a wicked problem, and this lens may offer new perspectives on solutions, further explored in box 1.

Challenge 1. The political legacy of military authoritarianism

The system of governance operated by the Myanmar military at the time of peace dialogues in the early 2010s was highly centralized and unaccountable to the population. This made it difficult to establish representative and participatory processes within the peace architecture, weakening its ability to foster truly transformative outcomes.

Decades of military authoritarianism in the second half of the 20th century hardened divisions within society and deepened hierarchies of power along lines of class and gender as well as ethnicity and religion. The government stifled open dialogue and produced a fractured political system in which many groups led their own populations and pockets of territory in different ways—from supporters of the NLD, largely concentrated in ethnically Bamar urban centers, to large and small EAOs in border regions with varying aspirations for self-determination, to the Myanmar military. Myanmar’s ethnic nationality populations have often felt doubly marginalized, both by the widespread lack of respect for citizens’ rights and by an unequal system that prioritized the economic interests, cultural identity, and legal status of privileged members of the ethnic majority population. The overall fabric of governance, including the management of diversity and ethnic nationality rights and status, remains a challenge. Without addressing these fundamental problems, peace will continue to be elusive.

Majority-minority power-sharing has been an historically intractable issue that has prevented a political model from taking shape which can satisfy constituencies across the country. In this context, a focus on ethnic nationalities in Myanmar has typically been associated with ethnically defined control over territory. This approach hits barriers where ethnic categories are arbitrary (as seen in the formal recognition of 135 groups inside the country) and where claims to authority overlap.[23] While some discussion around peacebuilding emphasized the need to allow local groups to administer identified enclaves or zones, the increasing dispersion and diversity of ethnicities across the country mean that long-term solutions will require ensuring ethnic nationality rights rather than focusing solely on ethnic self-determination.

In the context of the NCA, power-sharing emerged repeatedly as an issue during discussions of federalism and constitutional reform. However, meaningful consideration of different models of devolution and the construction of a more inclusive national identity were not a sufficiently significant part of the peace process. In addition, assumptions around the roots of power are contested, with many ethnic communities refuting the fundamental legitimacy of the central state’s authority. EAO leaders pushed for federal arrangements for armed forces and a variety of governance systems at the local level. At the same time, the military, along with many national civilian leaders, proceeded to establish a centrally managed system of partial decentralization of responsibilities and functions with a limited scope for locally defined forms of power-sharing. Finding an appropriate form of democracy for both national and regional levels that is able to meet the needs of all groups to participate and be represented in power-sharing and governance must be a cornerstone of sustainable peace in the future.

Challenge 2. Weak accountability and shallow democracy

Successive postcolonial military regimes prevented Myanmar from developing an open, democratic, and pluralistic political culture. EAO and civilian leaders lacked the capacity and experience to develop effective solutions as challenges and roadblocks arose.

Another legacy of Myanmar’s successive military regimes was the lack of a strong culture of democratic dialogue that would have helped actors to negotiate the political issues facing them. The public’s experience of authoritarian culture also shaped the tenor of civil-military relations because the military and the civilian government were perceived as natural enemies, resulting in confrontation and a lack of interest in compromise.[24] Central issues proved extremely difficult to resolve, illustrating both the long-standing and intractable nature of the issues and the distance between the protagonists’ respective positions. The Myanmar military was unused to dealing with a political opposition, and the core leadership of the NLD had little experience in governing collaboratively through coalition. Neither side demonstrated strong accountability to the public.[25]

Establishing trust between opposing stakeholders is an especially critical aspect of negotiations in Myanmar, due to the prevalence of personalized politics and limited confidence in formal structures or rules. Trust-building was heavily emphasized during the negotiations under President Thein Sein. Aung Min, the former general appointed as a key broker for talks with EAOs, is seen as a successful example due to his ability to establish rapport with armed group leaders. Unlike his immediate predecessors, he was reported to be modest, straightforward, and willing to consider other points of view. At the time of the bilateral ceasefires, Aung Min shocked the KNU when the latter proposed 12 conditions and all of them were accepted immediately with no need to negotiate.[26] This approach to negotiation and progress was discarded when the NLD assumed leadership of the government. Little was invested in trust-building with EAOs by Aung San Suu Kyi’s government, and the attitude shown towards ethnic leaders was characterized as patronizing and insufficiently respectful.

EAOs exhibited various democratic and collaborative behaviors. Some had developed consultative mechanisms and skills in these areas. The KNU, for example, are considered to be relatively democratic and legitimate representatives of their people because of their governance mechanisms and consultation processes.[27] Others, such as the KIA and the KNPP, began to formally encourage responsiveness to civil society.[28] Many other groups are more autocratic, dominated by their military wings and offering little opportunity for communities to participate in decision-making or governance.[29] As a result, the legitimacy of EAO claims to represent their people varies, and respondents noted that they were often decidedly patriarchal and top-down in structure.

Challenge 3. Addressing drivers of conflict

Armed actors accrued considerable wealth and power from economic activities, both legal and illicit, under their control. Finding acceptable alternatives that would allow these sectors to be dismantled or formalized was not included in peace discussions.

The Myanmar military pursues both legal and illicit economic activities, the latter including direct or indirect involvement in the drug trade, “grey” resource extraction, casinos, and other enterprises. EAOs are also involved in many economic areas, in some cases developing long-term business ties with the military or their proxies. EAO leaders have been involved in legitimate local businesses, owning them or reaping dividends or revenue from them through taxes or protection money. Complex, cross-party relationships developed between adversaries involved in the informal or illicit trade of a range of goods, from jade and gold to timber and other resources.[30]

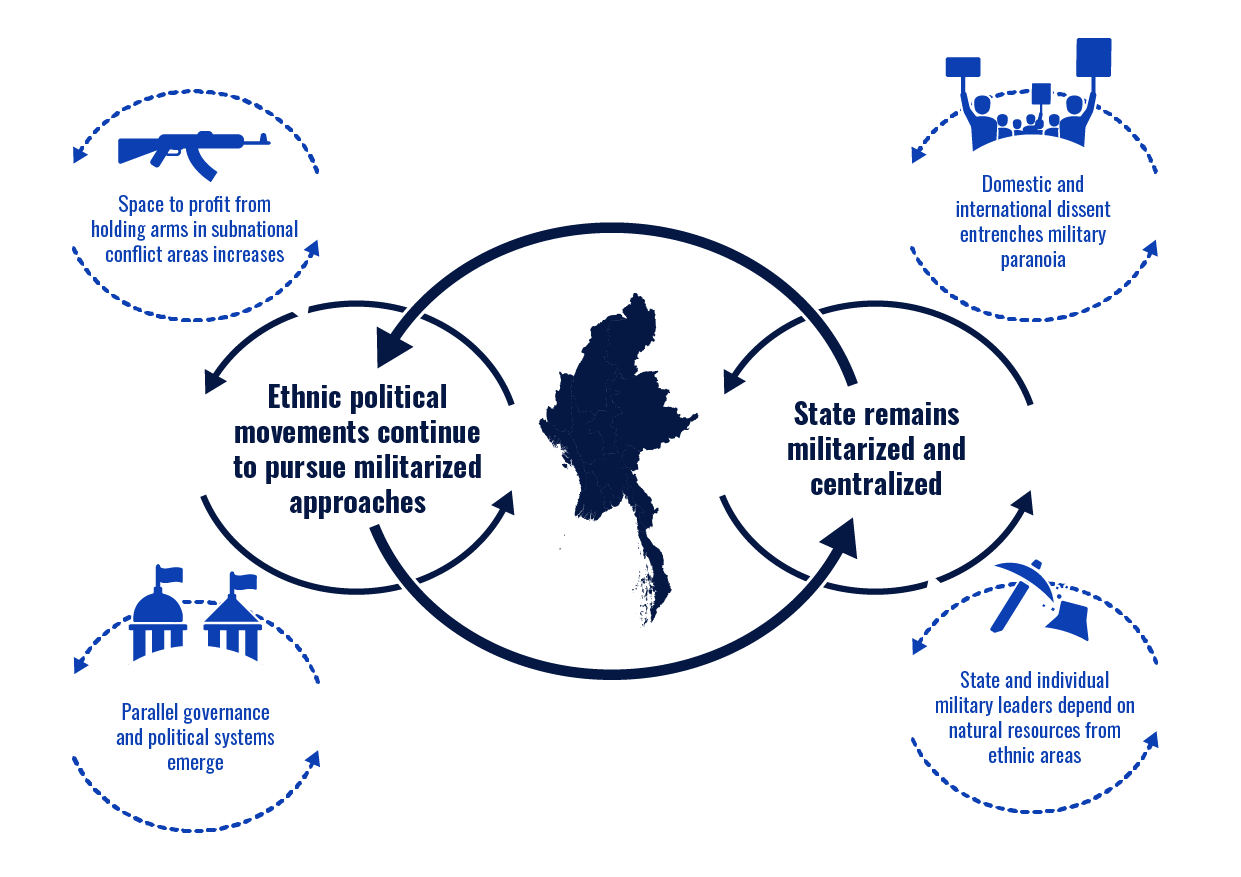

Informal wealth-generation activities have been crucial for many EAOs to increase their influence and resources and maintain the viability of their resistance. Economic opportunities have long been used by the military as an incentive to gain support from local power holders and to divide and rule ethnic opposition. Aung Min, a key figure for the military in the peace process, stated that his objective was to “make the EAOs rich” so that they would “automatically abandon their armies.”[31] The links between development and conflict are rarely so straightforward, especially in Myanmar’s contested areas where economic and security interests are closely entwined. This complexity is visualized in figure 4.[32]

While the challenge of dismantling these conflict economies was acknowledged by analysts and donors alike, the peace and development sectors never effectively engaged with it. According to a political analyst interviewed for this research:

For there to be a stable state later, there were obviously actors that would have to give up political power and wealth for the greater good. This meant needing to look at how to integrate the economies: the war economy involving drugs, extractive industries, casinos and the central formal economy.[33]

Little consideration was given to the transition of illicit and informal businesses into the formal economy, including income substitution for armed actors involved in illicit activities. Complex challenges over how to fund the eventual disarmament or integration of groups and militias into a federal or national military were also not approached. Past military strategy involved co-opting leaders rather than transforming the enabling conditions.

Challenge 4. Bringing in all the parties

The outcome of the NCA development process was an agreement that did not reflect the interests or incentives needed for all armed groups to sign it at the time. Consequently, it was unable, as an instrument, to bring an end to conflict.

Despite the variety and complexity of conflicts in the country, expectations for progress were based on the idea that “others will follow if the big guns are on board.”[34] Yet several key EAOs did not sign the NCA, including the northern groups: the UWSA, NDAA, MNDAA, TNLA, SSPP, and KIA. Within the NCA framework, Rakhine State was only represented by the Arakan Liberation Party, a small and divided group of limited relevance. The powerful and emerging Arakan Army was not involved, and the ethnic Rohingya had no voice in the process.[35]

A comprehensive agreement was merely aspirational given the EAOs’ range of relationships with the military noted above. Groups such as the UWSA chose not to join the NCA process, seeing little advantage in shifting from their existing position. Other groups wished to see specific elements included or conditions met before joining, perhaps the most critical being a halt to military operations. Some EAOs were formally excluded, although they often participated in informal meetings. While the creation of a functioning peace agreement inevitably requires a balance of power, with some parties ceding some power to others, sufficient incentives are needed.[36]

Respondents also pointed to the need to consider subregional diversity and intercommunal tensions that might affect a national peace process in the long term. The assumption that the KIA was the sole nonstate stakeholder in Kachin State raised concerns about the views of smaller ethnic communities such as Lisu and Shanni groups. Similarly, the highly complex dynamics and interactions within Shan State were viewed with insufficient nuance.[37] Other locations have a plethora of militias or Border Guard Forces in operation, and Western donors had limited insight into their structures, activities, and relations with the dominant EAO stakeholders.

This lack of engagement and understanding of other players meant that progress towards peace reinforced the formal effort but did not widen engagement, though efforts were made by civil society coalitions to add alternative perspectives through informal channels.[38] Significantly, progress toward building support for the peace process among the majority population was limited. With the process failing to gather momentum, hopes that it would build incentives for reform and marginalize hardliners did not materialize. Many senior military leaders and most of the EAOs outside the NCA appeared to maintain limited interest in genuine participation, instead using the peace process as an opportunity to expand and strengthen control.

Reflections on the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement

This section focuses specifically on the NCA as the primary vehicle for seeking a formal peace. It considers the agreement’s distinct components and analyzes the anticipated trajectories of progress.Just eight EAOs were the first to sign the NCA in 2015, and the Myanmar military, the civilian government, and donors each anticipated different trajectories for the agreement. A prominent prediction was that the NCA would provide the central architecture for a Framework for Political Dialogue, and that non-signatory EAOs would negotiate to join the process, eventually resulting in a peace accord that applied uniformly and comprehensively to all groups. Many foreign governments, also, assumed that both the military and the government of Myanmar shared a genuine interest in pursuing the peace process, and so would continue to work together as they had before signing the NCA. In fact, many expected that the election of the NLD would accelerate the process. This section explores aspects of the research that examine the NCA’s inability to deliver on its promises.

Reflection 1. The transition to NLD-led government

The NLD’s electoral victory in 2015 was a pivotal moment in Myanmar’s peace process, and it had significant implications for the institutions and leaders tasked with making the NCA work. Despite the climate of progress, poor alignment between the ongoing democratic reforms and the peace process resulted in missed opportunities and a loss of momentum. The transition to a new government was not sufficiently factored into the peace architecture, with major effects on its functioning.

Peace processes are never linear and rarely follow predictable paths. They depend on wider events and reforms that build political support and enable ceasefires to progress towards peace agreements. In Myanmar, the reform process that enabled the NCA was insufficient to take it further forward. Key stakeholders failed to demonstrate the understanding, flexibility, political will, and experience needed to redeem the commitments made in the NCA. Shortly after the NCA was signed, the NLD took over government and began to implement its own agenda of political transformation, principally inside the government and parliament.

The NCA process was largely controlled by military and government negotiators who appeared unwilling to make real concessions. Further problems stemmed from the absence of functioning links between the military and the government (exacerbated by the acrimonious relationship between Min Aung Hlaing and Aung San Suu Kyi). With the election of the NLD in 2015, the government side of the negotiations shifted from a unified presence with a single leader to a divided body made up of fractious military and civilian components. As one ethnic leader noted, “We basically had to negotiate with two parties; this was not based on principles but rather around personal disagreements between the leaders.”[39]

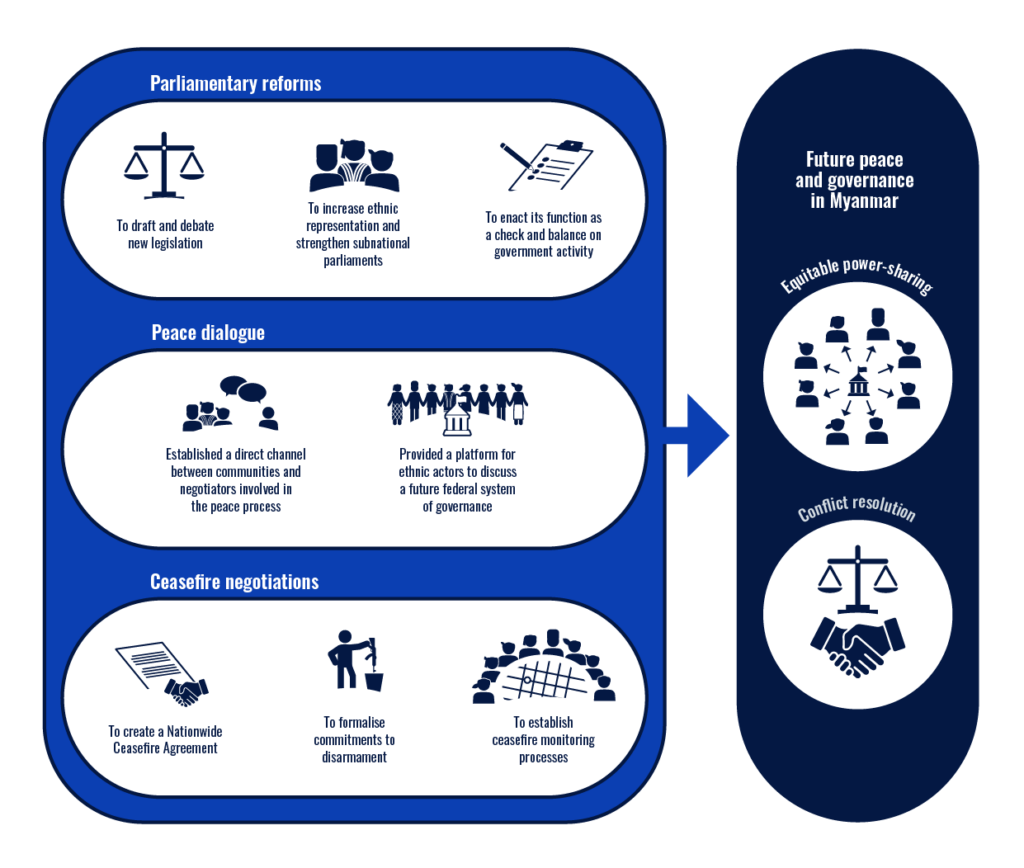

The government did not take firm responsibility for the existing process, inherited from the previous military-aligned administration which had rushed the signing of the agreement before the 2015 election. Neither did the government always demonstrate leadership in areas where it clearly had a moral mandate, as in the political dialogue process. Instead, amendment of the constitution, through parliamentary procedure and executive decision-making, was prioritized as the primary route for change, despite major overlaps with the core objectives and stakeholders of the NCA process (figure 5).

Meanwhile, the resources and influence of the existing peace architecture were dismantled: the Union Peace Central Committee and the MPC were replaced by a new body, the National Reconciliation and Peace Centre. As a result, the NCA lost political momentum at the national level. The so-called “10+10” meetings in October 2018 illustrate both the political stakes and the real risk of the NCA failing. The two-day summit brought together the government, military and EAOs to address a deadlock in NCA talks, and rebuild trust in the process to achieve a federal democratic union. The meeting did not resolve the issue and highlighted for many the inability for the NCA process to incorporate the divergent views of non-signatories into the NCA, nor to leverage other ongoing political reform processes.[40]

Other practical challenges emerged. Aung San Suu Kyi was reportedly a micromanager, wishing to know deep levels of detail and unwilling to devolve authority or entrust decision-making to others within the NLD.[41] The Myanmar military, for its part, did not take seriously its leadership role in the Joint Ceasefire Monitoring Committee (JMC) within the NCA (see below), failing to adequately address ceasefire violations and breaches of the NCA code of conduct. The autocratic approach of the commander in chief, Min Aung Hlaing, reflected the hierarchical culture of the Myanmar military. While a strong chain of command is necessary for an effective military, power within the Myanmar military was held by a very small leadership group, and this severely limited independent decision-making by the JMC on the ground.

The changes to the government’s approach may have reflected pragmatic political reasoning, including the simple assertion of control by the NLD, but they raise questions about how the transition took place and the new government’s understanding of the issues at stake. In other contexts, prior to elections, opposition leaders would engage on sensitive issues like the peace process to minimize disruptions. The lack of experience in managing transitions and in political leadership, alongside enduring hostility between military and civil leaders, may have played a role here. As one observer noted, under Thein Sein’s government, the peace process was accepted as a political process, while the NLD government viewed it more as a security issue, shifting responsibility towards the military. Ideally, the NLD should have been consulted early in the transition process, but this would have required the Thein Sein government to show some humility and the NLD to show interest in engagement. The NLD would also have needed a strong understanding of ethnic grievances and a willingness to nuance their view of national democracy as the solution at that point in time. The international community could also have offered advice as a “critical friend,” though it would have been difficult under the circumstances.

Reflection 2. Was the agreement too complicated?

The agreement that was ultimately developed was complex in its details and inflexible in its ability to respond to real context. As a result, the process moved slowly and risked losing buy-in.

A common view from respondents was that the NCA was overly complex and too ambitious. Box 2 outlines the many components of the agreement. Perhaps it should have focused more narrowly on ceasefire provisions. A related observation is that the political dialogue framework and the committee structures were also too complex and a departure from successful negotiations of the past (often between key leaders and dominated by the armed protagonists).[42] On the positive side, the structure was more flexible than it appeared.

A key ethnic nationality contributor to the framework also noted that an alternative structure for the political dialogue might, in hindsight, have been more effective:

Now, [in the political dialogue process] we would probably not put all of the political parties or the EAOs together by category. This was a mistake, as it meant the most powerful groups dominated [their own category]. It would probably have been better to have mixed groupings based on geography—Kachin, Shan, and so on—as these are the groups that will have to work together in the future, and it might have mitigated the power differential element.[43]

Observers noted that insufficiently comprehensive oversight of the different NCA streams caused a lack of coherence and undermined confidence in the overall process. It also made positive interventions difficult when progress faltered, like investing more negotiating energy at key moments or responding to trouble spots with renewed focus. Such interventions require flexibility and a willingness to follow the ebbs and flows of the negotiations, recognizing when progress is occurring while simultaneously working on the obstacles.

Reflection 3. Disunity among EAOs

Many observers thought that more unity would have increased the collective leverage of the EAOs in negotiations. It could also have increased the likelihood that more EAOs would sign the NCA after 2015. Instead, following the NLD’s accession to government, there was a fracturing of the ethnic stakeholder side.

Respondents noted a combination of factors that influenced this dimension, including the diversity of EAO positions, expectations, and demands. A critical demand of some EAOs (e.g., the KIA and the TNLA) was the complete cessation of Myanmar military operations before they would sign the NCA or engage in negotiations.[44] Prior to the signing of the NCA, the United Nationalities Federal Council was established to represent groups that sought to engage in the peace process and provide a platform for inter-EAO coordination. After 2015, the differences in proximity and participation among different EAOs allowed political divisions within the NCA process to grow. Unity in the EAO bloc was further complicated by the post-2016 split in the government negotiation side between the new NLD administration and the military leadership. The establishment of a new Wa-led alliance in 2017, the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee, built closer links between several powerful northern-based groups and Chinese influence in the peace process grew. This led to the collapse of the United Nationalities Federal Council and thus effectively halted negotiations with the main non-signatory EAOs.

At individual and institutional levels other factors conspired to prevent greater unity, including the uneven quality of leadership across the different groups, with tensions often arising from civil-military divides, self-interest, and the military’s continuing divide-and-rule tactics. In this regard, one respondent noted that it was unfortunate there had not been a central “Aung Min type” negotiator on the side of the EAOs, but this was impossible given their many differences. As noted by a key ethnic participant in the formal peace process:

In the beginning, we were able to keep the EAOs more unified together, but during the NLD government phase there were multiple camps, and so negotiations became secondary. The NCA process at this point tended to harden positions. Though everyone basically agreed on the text, there were significant divisions within the non-signatories. Some personalities were very difficult to work with, and the KIA were very upset, as essentially their leaders had come to Yangon in 2015 and agreed on the NCA text but were then rejected from participation.[45]

Foreign governments and aid agencies also played a role in encouraging or hindering the various EAOs’ participation in peace talks at the time. Many Western countries that had invested in Myanmar’s trajectory toward liberal democracy saw greater buy-in to the peace process amongst EAOs as one aspect of wider progress. Many EAO leaders did not share this view and felt that Western pressure to agree to the NCA was counterproductive.

Reflection 4. Neither nationwide nor inclusive

Further along in the NCA process, problems developed from the issue of who was or was not involved and who was or was not bound by the agreement. The NCA did not include major EAOs, which lessened its effectiveness in reducing levels of violence in Myanmar.

The NCA went beyond a conventional ceasefire document by including a major commitment to political transition. A respondent who was involved in its drafting noted that, while it was a “game-changing” element, the call for transformative political dialogue was included in the NCA without the involvement of key political stakeholders in its design, suggesting that the NLD, and possibly other political leaders, could have been involved or consulted.[46] This emerges as a perennial peace process dilemma: whom to include and at what point in the process? Involving too many people too early may scuttle a vulnerable process by alienating other stakeholders (in this case the military) who fear a loss of control. What’s left is a tension between a placeholder for longer-term political aspirations, and having a more structured and potentially prescriptive process that leaves less room for flexibility in its evolution.

A further ambiguity related to the recognition of previously signed ceasefires, prompting some EAOs to question why they should join the NCA at all. This allowed some to stand on the sidelines and observe before committing themselves. Others may have thought they would have an advantage if they waited to negotiate until the NLD took over the government. Both perspectives focused primarily on the ceasefire component, without giving due weight to the possible advantage of a collective EAO negotiation within the political dialogue.

In addition to complexities surrounding the inclusion of EAOs, political parties remained peripheral to central NCA negotiations, uninvited to meetings and generally only informed after agreements were reached between the army and EAOs. In many areas of the country such as Rakhine State and parts of Shan State, opposition to the central authorities had shifted from armed groups to political parties. The NCA was not set up to encompass these, but neither did parliamentary process make room for these voices to be heard. The approval (possibly symbolic) of political parties was sought in the later part of the NCA, such as after the 10 + 10 meeting, but their marginalization reinforced the idea that armed groups were the key decision-makers.

Reflection 5. National ownership and central government oversight

Efforts to assert central government control over the NCA process added further complications.

Myanmar’s leaders were clear that they had embarked on what they termed a “nationally owned peace process.” According to the Myanmar Development Assistance Policy, taken forward under the NLD government after 2015,

The first objective of the Economic Policy of the Union of Myanmar is to support national reconciliation and the emergence of a united federal democratic union… All development assistance should be designed and delivered in such ways as to align with and support Myanmar’s nationally owned peace process and national reconciliation efforts. (28-9-2017, Section 2.2)[47]

This policy was operationalized through a number of mechanisms intended to ensure central government oversight, and in some cases direct decision-making authority, over external support for peacebuilding activities, from funding flows to technical assistance. A well-known example of such a mechanism is the Joint Coordination Body, an agency established in 2016 to scrutinize funding allocations and spending limits on activities related to implementing the peace process. The goal, as stated by Aung San Suu Kyi, was to “fairly and effectively manage the funds by coordinating and allocating them to the sectors based on the real situation rather than donor-oriented ones.”[48] The Joint Coordination Body featured equal representation of government and EAOs, though commentators have suggested that real decision-making influence rested with the government. Within the context of the multi-donor Joint Peace Fund, there was concern as to what such government oversight might mean for control of their funding, as well as potential risks in sharing sensitive information on EAO and civil society organization (CSO) fund recipients.

The policy of national ownership meant that the structures and procedures of the peace process were less influenced by common practices from other contexts, nor was there international involvement in monitoring or mediation. Ultimately, the progress and achievements of the process did not follow an internationally recognized trajectory (ceasefire first, followed by a political settlement), which may have resulted in false expectations and misinterpretation by the international community of observers and supporters. National stakeholders were unclear about the meaning of a national peace process in the Myanmar context, where the issues to be resolved had not been fully expressed within the peace agreement, and the concept of national identity and the legitimacy of the state itself were fundamentally disputed.

Reflection 6. Problems with monitoring and enforcement

The part of the NCA that sought to monitor and enforce the ceasefire would be a key factor in its overall success. Two major aspects complicated its functioning: its complexity, like the rest of the NCA, and the lack of genuine will amongst all conflict actors to reduce violent incidents and allow third-party monitoring.

The Joint Ceasefire Monitoring Committee (JMC) was established in 2015 as a critical element of the NCA. Through a complicated and multilayered system of committees and secretariats, the JMC mechanism aimed to establish accountability and manage disputes or ceasefire infringements at the local, state, and national levels. The highest level of dispute resolution rested with the chairman, General Yar Pyae of the Myanmar military. Thus, with no third party or neutral mechanism, a structural dead end was created if the military refused to compromise or acknowledge fault, frustrating the EAOs and resulting in “a finger-pointing experience [with EAOs and the Myanmar military] blaming each other.”[49] To some extent, the external role was intended for civilian parties, but their role within the JMC structure was not well understood by armed actors, creating further tensions.[50]Given limited trust between groups, it became an arena for further disputes between the parties, with the balance of power firmly tipped towards the military. Some observers considered the setup more suited to conventional interstate wars than to asymmetric conflicts involving nonstate groups and guerrilla armies.[51] At a practical level, an example of how this dysfunctionality worked was provided in Karen State:

The Tatmadaw had entered and used a monastery’s grounds for military purposes. This is exactly the sort of violation supposed to be addressed at the local level, but it had to go all the way up through the layers to the Union level for a decision. This would take months or never happen. There was a clear mandate for the JMC at the local level, but the reality did not accord with the intentions. The civilians involved were clear regarding their role and these issues, but the military did not accept their perspectives.[52]

Demarcation, security sector reform, and de-mining were all included in the JMC mandate. Given the complexity of the issues and their contentious nature, as well as the inevitable challenges of moving forward in each aspect, considering separate approaches and institutions might have been a more effective strategy. The JMC and its ceasefire monitoring also appeared isolated from ongoing political dialogue, which was regrettable given its critical role in the roadmap to peace. This isolation was given greater prominence by the NLD government’s lack of interest in the JMC, which they appeared to consider a purely military matter. Civil-military tensions certainly existed, but the lack of interaction was a missed opportunity for NLD engagement with the military and sent the wrong message to NLD ministers.

The many failures and few successes of the JMC raise questions as to whether there was any real commitment to the peace process by the Myanmar military. While there were violations on all sides, respondents close to the JMC felt that the Myanmar military were uninterested in abiding by the rules, as evidenced by their continued construction of roads and military posts in ceasefire areas. Some suggested that this was simply another tactic of the military to prevent progress in the NCA.[53]

Reflection 7. The role of civil society

Civil society had varying levels of influence on the initial development of a nationwide agreement, particularly in some ethnic majority regions. Civic leaders were not given a formal role in the peace architecture set out in the NCA, relegating their ideas and contributions to “Track 1.5” spaces, including the Civil Society Forum for Peace.

CSOs in different geographic areas exerted a strong influence on EAO behavior, such as raising awareness of conflict-related injustices and advocating respect for human rights. While this type of engagement generated space for discussion of these grave issues, it also alienated some stakeholders, with some respondents suggesting that a more subtle approach would encourage greater behavior change. They posited that civil society actors worked more effectively across divides than EAOs in the peacebuilding sphere, so they could push the agenda forward and encourage dialogue among the EAOs.

CSO leaders also noted the relationship between a vibrant civil society and greater recognition of civic issues by EAOs, a dynamic that was particularly visible in the KIA, KNU and KNPP. In Kachin areas, civil society had significant power, and some leaders were very courageous. The Kachin Baptist community leader Reverend Samson, for example, confronted KIA leadership, challenging them to reflect democratic principles in their structures and to hold elections. Respondents to this study noted that in areas where civil society was weaker, leaders were more likely to end up with a military mindset at the state level. The Myanmar military themselves implicitly acknowledged this as they tried to capture civil society, and they often attempted to put “military civilians” into mechanisms and CSOs.[58]

Civil society also influenced the NCA process, often playing a technical role influencing policies for the political dialogue framework, and playing leadership roles on humanitarian issues.[59] The Joint Strategy Team was formed by nine civil society organizations to deliver humanitarian relief to those affected by the resumption of fighting between the KIA and Myanmar military in 2014. This network was able to deal with and manage their own local stakeholders in their own areas, preventing conflict, negotiating access, and encouraging open communications.

The political transition in Myanmar also brought forth several key challenges for civil society actors. The election of the NLD brought a reduction in civil society space, attributed by respondents to the former’s distrust and adversarial view of CSOs. Furthermore, poor relations between the NLD government and a predominantly ethnic-based civil society sector focused on conflict issues led to a bigger division in the civil society space: between Bamar organizations connected to the NLD and its political agenda, and ethnic actors who were less supportive of the central government.